In March of 2024, in Toba Tek Singh town in the central-eastern province of Punjab, a 22-year-old woman named Maria was brutally strangled to death in the presence of her family members, including her father, in what appears to be a horrific case of honour killing.

According to local news networks, the gruesome act was captured on video, showing Maria being choked while other family members, including her sister-in-law, looked on seemingly unperturbed. The footage portrays a scene of unimaginable horror, with Maria’s brother identified as the perpetrator, while another family member filmed the heinous act.

In a chilling testimony to the local news network, Maria’s brother Shahbaz and sister-in-law disclosed distressing details about the events leading up to her tragic death. They revealed that Maria had confided in the family about being raped. However, instead of receiving support, Maria was murdered in cold blood.

This most recent case echoes that of the highly publicised murder of social media star Qandeel Baloch who was also killed by her brother. Baloch’s death in July, 2018, fuelled outcries from human rights organisations across Pakistan.

Data from the UNFPA reveals that a staggering 39% of women aged between 19 and 49 in Pakistan face physical and mental abuse, and that 80% of married women suffer from domestic violence, consisting of verbal abuse (76%), slapping (52%) pushing (47%) and kicking (40%).

Then, in 2022, the story of two sisters with dual Pakistani and Spanish citizenship, who were allegedly killed by their husbands, uncle, and brother in a so-called “honour” killing shortly after being tricked into travelling to Pakistan, hit the international headlines.

Aneesa Abbas, 24, and Arooj Abbas, 21, were strangled and shot dead after arriving in the eastern city of Gujrat with their mother, Azra Bibi. According to reports, the sisters were being pressured to help their husbands, whom they were forced to marry in 2021, apply for spouse visas to travel to Europe.

It is alleged that Aneesa and Arooj were murdered because they refused to comply. Both women had wanted to divorce their husbands, who were also their cousins, so they could remarry in Spain.

Horrifically, data from the UNFPA reveals that a staggering 39% of women aged between 19 and 49 in Pakistan face physical and mental abuse, and that 80% of married women suffer from domestic violence, consisting of verbal abuse (76%), slapping (52%) pushing (47%) and kicking (40%).

The situation is compounded by social and cultural factors that embrace victim blaming – hiding incidents to prevent family ‘dishonour’ rather than tackling the problem. Commonly, violent acts or cases of harassment result in women being kept in the home, away from unwanted male attention, and in extreme cases, like Maria, in death.

Undermining empowerment

It’s a reality that simultaneously embarrasses and frustrates activists seeking to empower women in the region, who are not only dealing with perpetrators of violence, but a culture that enables such practices because they are embedded within the very fabric of society – namely, the family.

The issue is further compounded by a lack of financial inclusion. A large proportion of women rely entirely on their husbands or their male relatives for all financial activity, as men form the bulk of bank account holders, and women more often than not, must seek male approval on any transactions.

It was this very dilemma that led Rehan Butt – founder of Instaful Solutions – to look at alternative methods of protecting women from the risk of violence and harassment across all social stratas in Pakistan.

One in two Pakistani women do not report violence; we know cultural, societal constraints and not-so-uncommon victim blaming play a role, although digitisation and information technology are slowly changing this trend.

Rehan Butt, Instaful Solutions

With a strong background in the international insurance industry, Rehan has worked across various functions in roles with AIG, American Life and MetLife, he then pivoted to focus on inclusive, digital and micro insurance. He says: “In my inclusive and digital journey since 2013, I have worked on providing simple insurance products to millions of low-income customers in emerging markets across Asia and Africa.”

Mobile technology and empowerment

The ‘aha’ moment, which drove Rehan to found his own insurtech started in 2023 began with a report about a leading bank detailing attempts to improve Pakistan’s financial inclusion for women. He explains: “Just over a year ago, I read a news story about a large bank launching a women-only banking proposition. The article quoted a senior banker explaining the difference between financial inclusion and true independence and empowerment. She mentioned that although over a third of the bank’s accounts were owned by women, more than 80% were joint accounts with their husbands, meaning many women were not utilising banking products and services independently.”

Then the video of Maria’s murder went viral in Pakistan and it both haunted and motivated Rehan to take affirmative action. “This incident made me understand that true independence for women is totally compromised by harassment. It also made me realise that addressing those issues could significantly advance women’s empowerment and inclusion. This was the trigger that resulted in us developing an insurance solution to help protect women from harassment aiming to support their independence and empowerment.”

The goal was to create a product that would provide as many women as possible with a safety net – regardless of whether they were independent city-dwelling earners or unemployed and living rurally. If they had access to a mobile phone, they could receive the service.

“I knew that the middle-income segment in emerging countries, which constitutes 50-60% of the addressable market, faces significant everyday risks but remains un- or under-served,” he says. “I saw a great problem to solve. How could we put measures in place that would reduce the risks of violence and harassment, and would simultaneously be affordable, available to all women, and enable them to have some sort of financial help to cover medical expenses in the event of an attack?”

Digital solutions for traditional problems

This determination led to the creation of lyzil – a digital B2B2C platform that provides an online safe place for women outside of their home environment, and is in cooperation with women’s empowerment charities as well as local law enforcement and insurers.

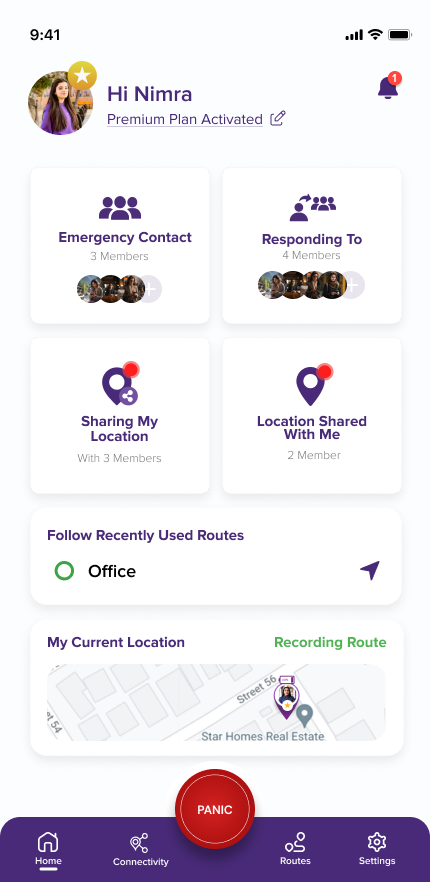

For the same price as a bottle of water a day, or just over US$1 per month, a woman can be connected to the app that links to an emergency call centre. By simply pressing the emergency button on her mobile phone, the call centre automatically triangulates her GPS, providing her location to Iyzil’s team, and within 30 seconds her phone will ring. If the call is unanswered, the assigned emergency contact is alerted and also, where considered necessary, local law enforcement.

The app enables women to have a point of contact beyond the boundaries of their families, and gives them a vital lifeline in the event of an emergency. Butt explains: “Our mission is to serve the risk needs of low- and middle-income segments – those with daily household income up to $30/32 with majority earning between $2 to $8 per day – using a product-agnostic, problem-focused business model that leverages digital technology.”

Rehan also believes technology is the key to freedom for women facing otherwise oppressive situations. “I will cite a UNFPA report that shows one in two Pakistani women do not report violence; we know cultural, societal constraints and not-so-uncommon victim blaming play a role although digitisation and information technology are slowly changing this trend. Our solution acts as a supportive buddy providing instant, one-click response which is crucial during distress when dialling a number might not be feasible or possible.”

Bolstering legal protections for women

For women in the US or Europe, it seems crazy that an app run by a private company could be the one piece of technology to save a life in the event of extreme domestic abuse. Surely, an emergency call to the local police station would make more sense?

Sadly not, explains Mashal Rehman, who handles outreach for Iyzil and is seeking to enlist support for the project in Pakistan’s business communities and charitable organisations.

She says: “In Pakistan, the reality for women facing domestic abuse is very different to those in the West. Often, women are pressured to keep such traumatic experiences private. Cultural expectations make it difficult for them to seek help openly. In these scenarios, many turn to us for support.”

Mashal says the struggle to reach out for help is compounded by a deeply ingrained sense of privacy. “When a woman feels endangered and calls the local law enforcement, the response can be uncertain – and her hesitation often stems from the fear of not getting the help she desperately needs.”

Mashal also points out that calling the police doesn’t guarantee an immediate response. In fact, typically 24-to 48 hours is normal – a delay that could – and has – proved fatal. Instead, Iyzil provides women with an emergency button that, within moments, will alert a trusted person, and will issue a report to the local law enforcement agencies, which have an agreement to prioritise all alerts from the app’s call centres.

“Our organisation has forged strong connections with higher authorities through MOUs, ensuring that when we step in, these women are given the priority they deserve. Imagine the despair of a woman waiting 24 to 48 hours for a response after reaching out on her own? But through us, because of the agreements we have in place, the response is swifter. This priority treatment can mean the difference between safety and continued suffering.”

She continues: “We have features that provide the user’s location and battery percentage. Additionally, our application allows users to add emergency contacts, such as a brother, sister, or colleague. These contacts receive the same notification on their phones, enabling them to assist in rescuing the person in need.

“We are also working on introducing mesh networking. This feature will allow volunteers in the same city to be alerted when someone nearby needs help. By leveraging this network of volunteers, we aim to create a community of support, ensuring that help is always within reach.”

Empowering women through safety

Though Iyzil has proved itself useful in extreme situations, it has a wider range of use cases linked to empowerment for women. As Rehan explains, very often, transportation can be treacherous for women, with the rates of rapes and assaults on busses and in taxis on the rise.

“The app works well for women who find themselves in a difficult situation in a taxi, for example,” he says. “It’s not uncommon for a woman to notice that her taxi driver is taking her on a different route. He might make the excuse that it’s a short cut. In this case, a woman can hit the panic button, and within 30 seconds, she will be connected to the Iyzil call centre. The operator will talk her through the situation and track her GPS. She can also ask for a call to be placed with the police. This warning to the driver is very often enough of a deterrent and will keep her safe.”

Rehan explains that this third party facility is essential if women are to be able to move around freely and have a job. “All too often, if families are alerted to such incidents, the woman can be ordered to stay home and give up any form of independence. This ruins her ability to achieve financial independence in the long term.”

He says Iyzil has also been used to prevent sexual harassment in the workplace – another endemic problem that often results in women being forced to leave their jobs to prevent a scandal in the family. “If a woman is approached by a man in the workplace and is facing harassment, she can hit the emergency button on her phone and will receive a call within seconds. This gives her the opportunity to make her getaway from the situation. Iyzil data logs all incidences – and these can then be used to build a legal case against men who are sexual predators, if necessary.”

Physical and mental support for recovery

While the risk benefits are clear, the insurance side of Iyzil is also a game changer for women who require hospitalisation and therapy in the aftermath of an assault. A typical package will pay out 100,000 Pakistan Rupees (US$360) which would cover the cost of treatment or even surgery in a private hospital, as well as sessions with a mental health trauma specialist.

“Fixing someone physically after a violent assault is one thing – but mentally, these women need help to recover. It’s very important to address this because there is a strong victim-blaming culture present – and this can seriously hinder women from recovering their independence,” Rehan says.

A pathway to more successful convictions for sexual assault and rape would also be a game changer for women in the region. According to reports, despite Pakistan strengthening anti-rape laws in 2016 and 2020, introducing longer sentences, and establishing special courts to expedite cases within four months, the country’s conviction rates in rape cases remain below 3%.

Currently, many rape survivors and their families, fearing the stigma associated with a trial, often settle out of court. They frequently face threats and coercion from their attackers, their own families, as well as the wider community.

Distribution and outreach

So far, Instaful Solutions is in talks with a number of large corporations and insureds to offer Iyzil as an employee benefit. But to ensure distribution in poorer areas, the company has also partnered with charitable organisations championing women’s rights so that the service can be ‘gifted’ to those in need.

Mashal explains: “We have launched a CSR initiative aimed at bridging financial gaps and supporting women from marginalised communities. Through this programme, individuals who are financially stable can sponsor the application for women who cannot afford it. For example, if someone buys six licences, we provide these licences to six women at no cost.”

She continues: “Our goal is to build a community where women support each other. If I am financially secure and know someone in a rural area who needs this application more than I do, I can sponsor it for her. Additionally, we allocate a percentage of our earnings to provide free access to women who cannot afford it, ensuring that more women can benefit from this support regardless of their financial situation.”

Fighting fear with technology and accountability

There are plans in place to take the product across the Sub Continent and into Africa in the near future. Rehan says: “After a meaningful expansion in Pakistan, we plan to take this solution to other regions facing similar challenges. Our focus will initially be on Nigeria, Kenya, and Bangladesh. These countries share similar challenges and/ or cultural contexts where women often face acts of harassment and barriers to reporting them.”

Mashal is positive about the potential of Iyzil to have a transformative impact on the lives of women in Pakistan and beyond. She says: “I believe that our fight is fundamentally against fear. We aim to hold people accountable for their actions. Imagine the impact when people realise that women now have a platform to report abuse, to tell others about their experiences – and that helps to bolster legal recompense?”

She adds: “This is not just about deterrence; it’s about empowering women, giving them confidence that they have a voice and a way to seek help. Our efforts are making a tangible difference, instilling fear in those who would harm and courage in those who have been silent for too long.”

lyzil in brief

The solution includes prevention through a panic button alert and restoration through insurance.

At-home threats: If a woman faces domestic violence, she can press the panic button on her mobile app. This sends an alert with her mobile number, GPS location and battery position to our system. Within 30 seconds, our team calls her and based on her instruction, notify her first responders or the police.

Travelling threats: In case of harassment during a taxi or ride-hailing service, pressing the panic button triggers an alert, prompting a call from our team, which deters the driver and provides immediate assistance.

Workplace threats: For young professionals facing harassment at work, pressing the panic button sends an alert and our team calls her, helping her exit the situation safely.

In terms of restoration, the insurance covers treatment for physical injuries and up to three sessions with a leading psychotherapist or psychologist for the psychological injuries.

Report by: Joanna England