If there’s one thing the COVID-19 pandemic has clarified, it’s how many people yearn to ditch their daily commutes forever and, equally, how many companies are scrambling to reduce commercial office space in favor of expanding remote workforces. What’s less certain is how this paradigm shift will affect the motor vehicle and insurance industries over the long run.

For innovators in the emerging autonomous vehicle (AV) market, the future looks bright regardless of the ultimate purchasing trajectory. That’s because these visionaries don’t necessarily see AVs in every garage.

Instead, they envision a variety of adoption possibilities. For example, some people may own an AV and rent it out to a ride-hailing service when not in use. Others may primarily be ride-hailers and rent an AV directly when they want to take an extended road trip. Commercially, AVs offer businesses and mass-transit authorities more cost-effective and adaptive options for moving goods and people.

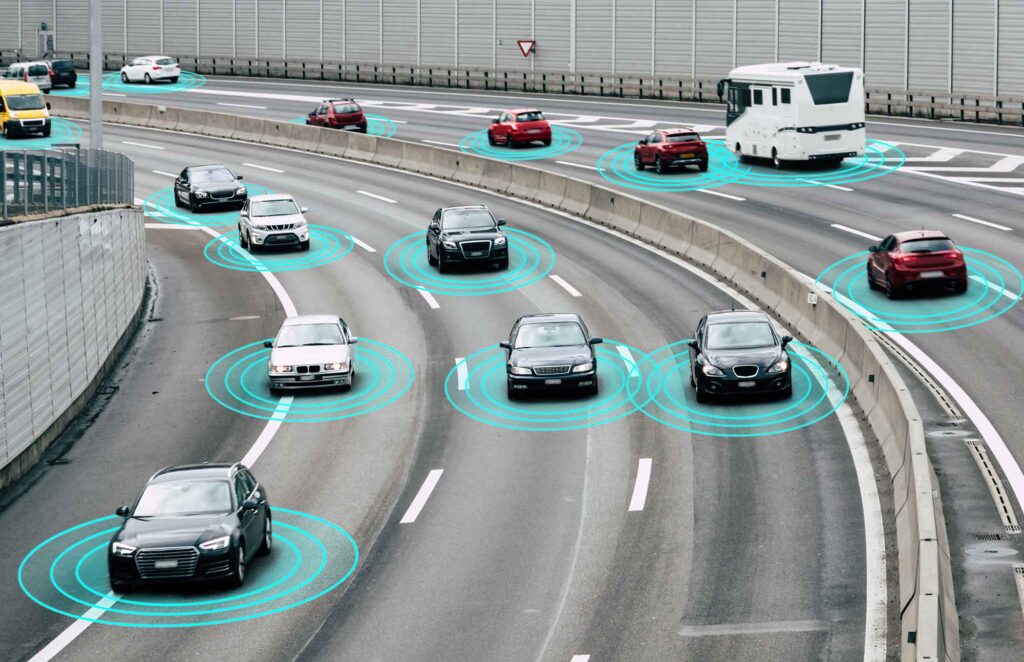

No matter how reality plays out, there’s one certainty for insurers: AVs signal even more industry disruption ahead.

To understand the current and future coverage opportunities, along with the challenges yet to be addressed, this multi-part blog series will provide insurers with relevant insights into the present status of AVs and where the industry is likely headed over the next decade.

Understanding the new AV taxonomy

Let’s begin with a brief overview of where we are along the driverless continuum.

The most basic vehicle autonomy features are the driver assistance technologies available on many makes and models of new cars today. These include lane-keeping, accident avoidance, and adaptive cruise control. This is defined as Level 1 autonomy by the Society of Automotive Engineers (SAE).

At the opposite end of the spectrum, Level 5 autonomy is defined as being fully automated, with even the steering wheel optional. This type of vehicle is smart enough to handle all eventualities, regardless of where it’s operated.

Today, Tesla says it’s “very close” to Level 5 for mass production and many other innovators, including Alphabet’s Waymo, are piloting Level 5 vehicles. Although it’s tempting to think of the cars as Level 5, the SAE doesn’t classify them as such because they don’t carry human passengers or deliver goods.

All other vehicle companies are somewhere along the spectrum in between. This includes Level 2, partial automation, where the driver stays alert to intervene; Level 3, conditional automation, where the vehicle notifies the driver when to intervene; and Level 4, high automation, where the vehicle is self-driving within a limited, geofenced area.

Road testing robotaxis

Making the leap from an empty Waymo car to AVs carrying people or delivering goods is now being road-tested across North America. For example, Voyager has permits to transport people within two retirement communities, one in San Jose, California, and the other in central Florida. Waymo has been piloting self-driving ride-hailing in Phoenix, Arizona.

Expanded road testing is also on the horizon. For instance, California’s Public Utilities Commission has issued permits to Aurora, AutoX, Cruise, Pony.ai, Zoox, and Waymo to participate in its Drivered AV Passenger Service Pilot program, which is the first phase of a state-wide AV on-road pilot. The second phase will be driverless.

In all the foregoing use cases, AVs are required to have at least one trained driver at the helm. In some instances, transport must be offered for free, such as for California’s Drivered pilot.

Underwriting implications on the horizon

For insurers, offering policies for current and near-term AV projects remains substantively the same as it has in the past. That’s because the experimental AVs still require drivers in them, making current coverage and underwriting models appropriate.

However, there are big changes on the horizon. When successively smarter vehicles are permitted on roadways on a larger scale, coverage will shift from today’s driver-centric model to becoming vehicle-centric as risk transfers to the AVs making the decisions.

In addition, there are thorny moral elements yet to be fully addressed, regulated, and insured. For instance, when faced with an inevitable accident, what rules govern the split-second choice an AV makes between damaging a parked car and hitting a light post? Further, how does an insurer underwrite such risks?